Composing New Urban Futures with AI

Jamie Littlefield

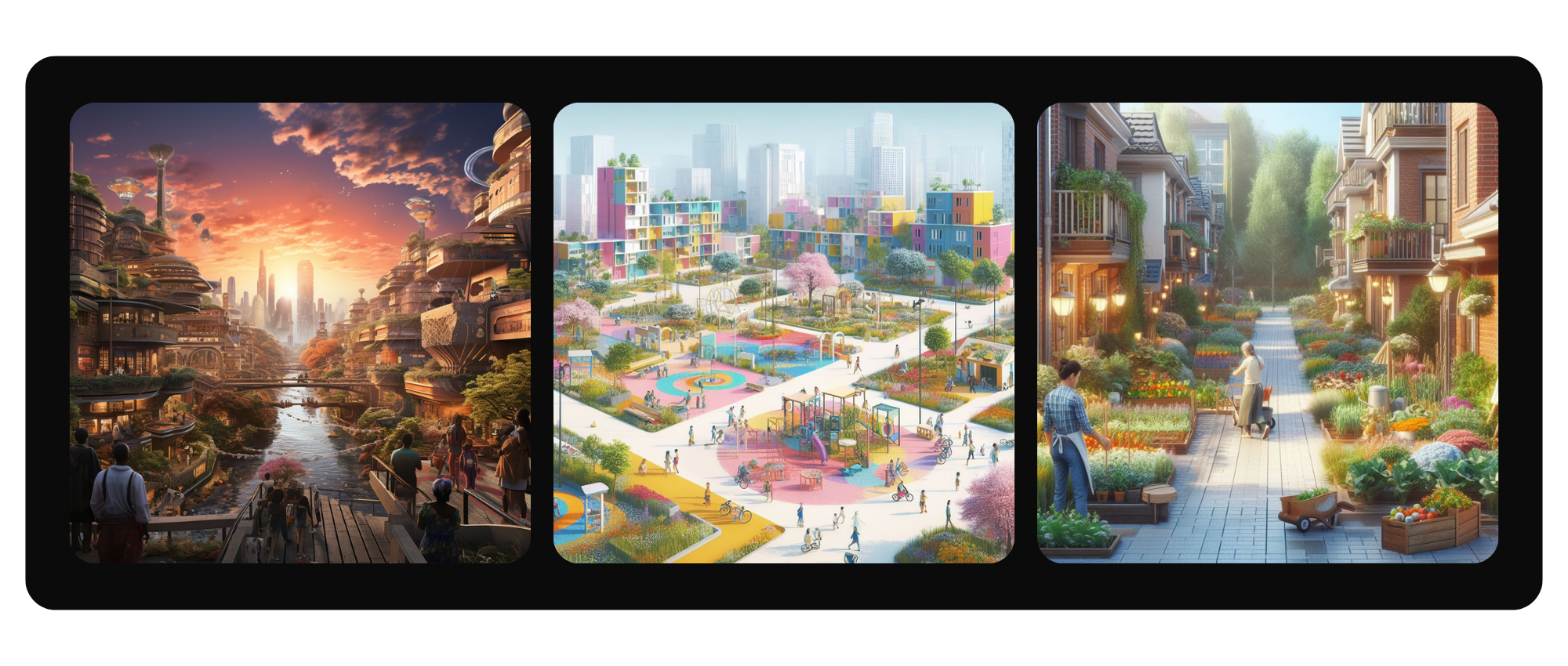

Three AI-Generated Examples of Speculative Design

To examine the potential uses of speculative design in text-to-image synthesis, I will consider three generative examples. Each of these small, exploratory projects turns a critical eye on the work I've conducted in the area of human-scale, eco-friendly city development as a non-profit communications consultant. These synthetic images are not intended to be polished pieces; instead, they are examples of tactical communicative interventions that can be rapidly created by underresourced groups.

Generative Example #1: Tracing the Projected Past

This first project demonstrates the ways that AI text-to-image synthesis re-creates the conventions of the past and provides suggestions for interventions based on speculative design. To begin this project, I examined how generative AI uses the cities of the past to create new images. Over 14 consecutive days, I entered the same four-word prompt in Midjourney's image-generating Discord server:

ideal neighborhood. photorealistic.

Out of the four resulting image options from each of the 14 initial generations, I consistently upgraded the first image (on the top left of the image results). I archived these synthetic images and analyzed the results, as shown in Video 1. By using the same prompt, I was able to develop a small corpus of synthetic images. Rather than analyzing images individually, examining a collection enabled me to begin identifying patterns.

Users may be tempted to assume that the resulting synthetic images would be widely varied, considering Midjourney's extensive training datasets. "Neighborhoods'' have long existed in a wide variety of countries, cultures, and decades. "Ideal" is similarly a vague descriptor that could apply to many subjective contexts. However, in this experiment, Midjourney recreated many of the same details for the prompt in different configurations. Its "new" output reflected patterns from particular subsets of the past.

Video 1. Fourteen synthetic images for the prompt "an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." (Source: Midjourney and the author. 2023).

After compiling these synthetic images, I examined the threads that connected them. I found that Midjourney was projecting a very specific interpretation of “ideal” and “neighborhood.” The corpus of synthetic images tended towards:

- Suburbanism. All of the images showed houses in suburban settings. There are no mixed-use options (i.e., combinations of different types of building uses such as commercial spaces, apartments. or local restaurants). Only one image displayed an urban area in the background.

- Americanism. Although the specific locale is unclear, the general aesthetics of the streets suggest that they are located in the United States (or possibly Canada). The architecture appears to be Victorian or Edwardian, a style popular in the U.S. from the late 1800s to the early 1900s and characterized by integrated details, varied rooflines, bay windows, and ornamental trims.

- Car-centricity. 100% of the synthetic images include cars using the public space in the street or sidewalk. By contrast, only 7% of the images included humans using these public spaces. No alternative transportation methods, such as light rail, scooters, or buses were identified. Additionally, only 42% of the synthetic images included usable sidewalks on both sides of the street (or one side if only one side was pictured) that would be unobstructed to a person using a wheelchair or pushing a stroller.

- Classism. All synthetic images featured large houses (generally 2-3 stories) in good condition with front porches and mature trees in what could be considered historic areas.

By drawing out the patterns in these images, we can start to identify how the AI text-to-image synthesizer is replicating a certain interpretation of the past. We can also begin to imagine how using these synthesized images in communicative contexts could produce value-lock by limiting the way we think about the future of neighborhoods. From the position of my own grassroots advocacy, I am concerned that using these images might contribute to the replication of the same type of exclusionary spaces that are already present in the built environment.

Applying a speculative design approach can help users imagine alternative ways to think about the same concept. Speculative design asks us to consider what alternative futures might be available to us. What if we were to create and circulate images of ideal neighborhoods that were not suburban, American, car-centric, and upper-class? What other types of neighborhoods might be considered "ideal" in the future? Speculative design practices can help users imagine built environments that are less predictable and less inclined to perpetuate value-lock.

One approach to generating more speculative synthetic images is to use AI as a tool for what Deleuze and Guattari (2013) call "rhizomatic thinking." Rhizomatic thinking is a non-hierarchical, decentralized cognitive approach that allows for multiple entry and exit points, much like the underground stems of rhizomatic vegetation (like bamboo, ginger, or mint). Unlike traditional, linear ways of thinking that seek a single "correct" solution or approach to an answer, rhizomatic thinking embraces complexity, multiplicity, and interconnectedness. In the context of AI-generated images, this means moving beyond mere replication or simulation of existing visual forms derived from the past. Instead, AI can be prompted to explore a larger array of possibilities, each branching off from the other, to create images that are not just novel but also speculative. These images can challenge our preconceived notions of reality, aesthetics, and even the limitations of human imagination, opening up new avenues for inquiry.

After noticing the patterns that emerged in the first corpus of generated images, I worked to create prompts that challenged text-to-image synthesizers to connect the concept of "neighborhood" to concepts that might be considered more distant and less linear. I experimented with new nodes like "Afrofuturism," "design for women," and "agricultural urbanism." The keyphrases used in these prompts were intended to serve as nodes for rhizomatic thinking, asking AI to tap into knowledge systems that were further from its original concept of "neighborhoods."

The resulting images (Figure 3) showed visual evidence of meaning drawn from alternative branches of thinking. In these images, we see: neighborhoods being used by many different people, bicyclists and pedestrians, shared public spaces, waterways, communal playgrounds, and different housing types. The synthesizers are still drawing from the past, but the generated content shows greater novelty because it is working with additional units of meaning. It is being asked to create connections between somewhat disparate pasts, between branches of thought that are less related. AI text-to-image synthesis allows users to intentionally and rapidly experiment with this style of rhizomatic thinking by generating content from multiple "nodes" through textual input, providing new possibilities for projecting alternative futures.

This brief exercise shows how AI users might employ a rhizomatic approach that would allow them to explore these questions in a rich, interconnected way. The resulting speculative designs can be edited and used to communicate new ways humans might exist in possible futures.

Generative Example #2: Speculative Design as a Tool for Value Negotiation and Identity Formation

As a practice, speculative design challenges communicators to tell stories that prompt discussion about who we are and what we value. By crafting narratives that exist beyond the present moment, communicators invite audiences to confront their own assumptions, biases, and ethical frameworks. This form of storytelling catalyzes dialogue, encouraging people to negotiate their values and reconsider their identities in the face of hypothetical yet plausible situations. In doing so, speculative design transcends aesthetic or functional considerations; it becomes a tool for social critique and identity exploration (Snow et al., 2021).

A place can be understood as a space that is filled with identity, culture, and shared references, bound together in time. Non-places, on the other hand, tend to promote the solitary identity of individuals disconnected from the people immediately around them (Varnelis & Friedberg, 2008). Examining the way places are connected to human values can help us identify what Rai (2016) refers to as "the competing rhetorical frames that circulate within and are tied to literal places" (p. 34).

For this example, I used DALL-E 3 to generate images that promote discussion about shared values around vacant property within my community. This project was done in response to local debate around the need for more convenient parking versus the need for more public spaces.

To generate the first synthetic image, I attempted to create distance between the subject and the anticipated audience. I chose the Eiffel Tower due to its status as a cultural symbol and its physical and ideological distance from Provo, Utah (i.e., it is known and loved but is distant and not considered "ours"). I used DALL-E 3 to generate a synthetic image, removing the public space picnickers and tourists enjoy below the tower and replacing it with a parking lot for electric vehicles.

For the second synthetic image, I attempted to close the gap between the place pictured and the anticipated audience. Using an iPhone, I took a simple photograph of an empty lot in a downtown Provo neighborhood. I then used DALL-E's outpainting tool to generate three images representing the materialization of different values: the construction of a parking lot, a bicycle-friendly community garden, and a neighborhood restaurant (Figure 5).

The purpose of these generations is not to needlessly provoke but to encourage community discussion. In these examples, I attempted to elicit responses that called for a deeper reflection on the ways public space is used and how that use reflects community values. Speculative design can draw people together around new kinds of inquiry: What do we gain when we use publicly owned space for parking? What do we lose? What does that say about us and our values? Are there specific circumstances where we might choose to trade the convenience of parking for another value, and how do we identify those circumstances?

Generative Example #3: Speculative Design & The Construction of Publics

This final example demonstrates how speculative design has the potential to create publics—groups of strangers who are united around a common text (written, visual, or multimedia). Drawing on the work of Dewey (1927), Habermas (1989), and Latour & Weibel (2005), writing researchers have long been interested in the ways that the creation of a text can construct a group of people and things empowered to take conjoint action (Gries, 2019; Moore, 2023, Preston, 2015; Boyle & Rivers, 2018). Such texts often prompt action through their circulation as a part of a larger rhetorical ecology, generating force through their association with other texts, rhetors, readers, histories, and materials (Rivers & Weber, 2011; Edbauer, 2005). By assembling a public with intentionality, communicators invite readers to see themselves and their involvement in an issue in a particular way and, potentially, work with each other to change the course of the future (Warner, 2002; Rice, 2012).

For this project, I wanted to communicate the urgency of responding to the environmental threats facing Utah due to climate change and highlight the need for alternative transportation methods like infrastructure that supports walking and bicycling. I chose to focus on the Great Salt Lake, a rapidly declining body of water receding due to recent droughts. For generations, the lakebed was used to dispose of toxic chemicals, which now threaten to become airborne as dust storms. I used Midjourney to generate a synthetic image displaying a dystopian possibility for the future of Salt Lake—a dried, cracked lakebed releasing toxins toward the city (Figure 6).

Following the practices of speculative design, I generated a companion image to suggest potential technologies that might be needed to mitigate this dystopian future (Figure 7). Refined in Canva, the image displays a prototype of a colorful mask combined with an AI-enabled air quality sensor that could be distributed to Utah children in areas experiencing toxic dust exposure from the declining lake. While K-12 students in our area are already required to stay indoors during recess on days with dangerous particulate matter readings, such a device could allow children access to outdoor spaces if air quality continues to decrease. These corresponding images invite readers to consider how the actions taken now may impact the nature of our community and the ways we exist within it in the future.

When combined with narrative, speculative imagery can serve as a rhetorical tool to gather the people and materials needed to enact change. In the case above, the images are intended to evoke emotion around an undesirable future and its technological implications and, potentially, generate the affective energy required to initiate public action. Here, again, the purpose is not to needlessly provoke but to identify ways that AI text-to-image synthesis can help us speculate about the future in order to change the present. In this case, generative AI is a valuable tool for rapidly creating narrative-based images and prototypes. It allows users to experiment with variations, pulling together materials of the past to imagine solutions for problems in the future. Most importantly, it offers new tools for communicators to pull together groups of actants around shared concerns.

In my non-profit work, the theories behind the construction of publics have proven particularly relevant. Our task is to assemble groups of people and things (publics) who are inspired to work together to reassemble the material elements of the built environment (streets, bike lanes, parks, etc.). Our recent air quality failures might be viewed as a breakdown in our attempts to effectively form publics—we have not yet been able to assemble the kinds of groups that are capable and motivated to address the environmental problems we face. By providing communicators the chance to rapidly experiment with different types of content creation, we may be able to more effectively assemble the types of publics we need.

It is important to note here that emergent technology may end up impacting not only what publics are formed but how publicness itself is experienced. That is, technology has the potential not only to change the membership of a public but to change the way people/things are drawn into a public and the way they experience that association itself. In Composing Place: Digital Rhetorics for a Mobile World, Greene (2023) points to the ways that technology may be used to create new kinds of public orientations:

"Rather than reducing the function of a digital text to its ability (or inability) to persuade a pre-given group of people, we should also attempt to understand how emerging technological infrastructures facilitate new formations of public-ness itself" (p. 40).

As technologies like augmented reality (AR) gain traction, humans may begin experiencing material places (like bus stops or public plazas) through interfaces that restrict or emphasize particular aspects of their experience with the built environment. Wearing AR headsets, one user may see factoids about local art in his visual field, while another may see evidence of local homelessness as a nondescript blur. Such applications function to "not only orient our physical position within a space but also our rhetorical position" (Crider et al., 2020, p. 9). Speculative design offers avenues for drawing users away from their individualized AR experiences and toward shared, material ways of addressing community challenges.