What Students Think about Generative AI

Jeanne Law, James Blakely, John C. Havard, and Laura Palmer

Discussion

As scholars and teachers in writing studies, members of our research team have witnessed the deluge of generative artificial intelligence tools that have swarmed mass culture since November 2022. Our students have witnessed and participated in this infusion as well. In the following section, we discuss preliminary findings, including initial passes at comparisons between populations of first-year writers who took the survey to undergraduate students enrolled in a 2000-level technical communication course, which is required for engineering and computer science majors at Kennesaw State University. This second population, which had 81 responses as of October 2023, consists of undergraduate students enrolled in TCOM 2010, an introductory technical writing course. TCOM 2010 is not currently part of the core curriculum, but functions as a service-learning course for Computer Science and Engineering.

Quantitative Analysis Discussion on First-Year Writers

When asked if they have heard of GPT or similar AI programs, student respondents reported overwhelmingly that they had (90%). This high number was expected, given the ubiquitous nature of “all things AI” on mass and social media platforms.

The data from our survey question three is of particular interest when we think of how first-year students may actually use generative artificial intelligence (gen-AI) in different rhetorical situations for writing. Figure 1 shows the results as of October 10, 2023. When broken down into five distinct categories, the data appears overwhelming in terms of use in academic writing. For example, 73% of respondents indicated that they never use gen-AI in their academic work. When we collapse the various categories of answers that report usage in varying degrees, however, we show that 28% do use gen-AI in some rhetorical situations of academic writing. While this data is preliminary and overarching, we believe that these percentages indicate consistency with answers to other parts of Q3, with 30% of students reporting that they use GPT and similar gen-AI in their personal writing (overall) but 70% never do. The variations on the Likert-esque scale are important, but, based on our interactions with students and our discussions with instructors, we believe the most significant numbers come from the actual reporting of use overall. For us, given the discussions of gen-AI around our university in most disciplines, we can assert that even a “sometimes” response may be all a student is willing to give, even as an anonymous answer. We have found in speaking to first-year students in our own courses and program, that they are reticent to admit to gen-AI usage for fear of being labeled cheaters or “lesser-than” in their writing abilities. Our anecdotal observations match what we believe are consistent survey measures of the attitudinal construct.

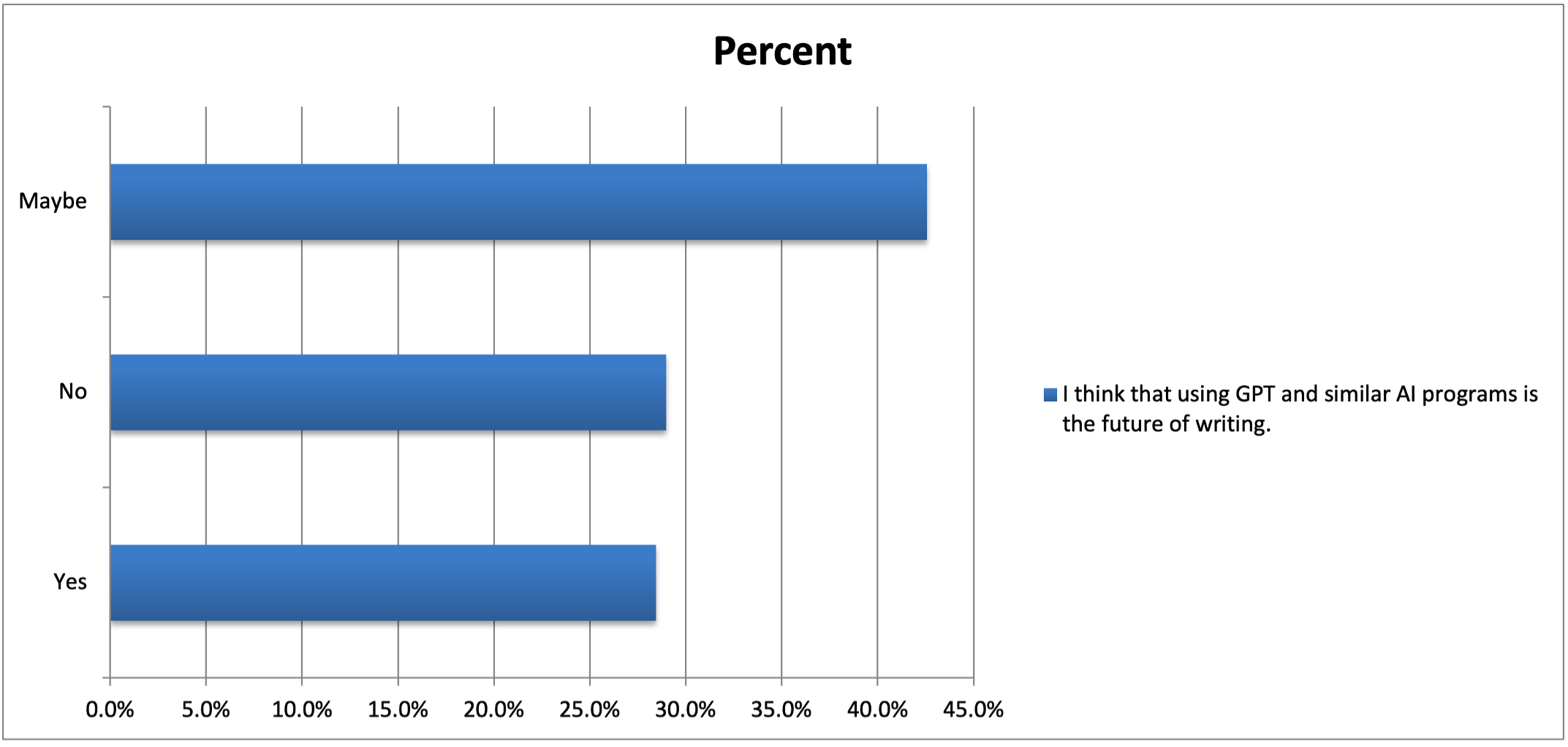

Students showed interesting splits when asked if generative artificial intelligence is the future of writing. In answers to this particular question, students were almost equally opposed in terms of yes and no. Figure 2 shows that 28% of students believed that gen-AI is the future of writing, while 29% definitely did not. Again, the majority of students fell in the middle, with 43% answering maybe. Figure 2 shows consistency in responses related to other survey questions.

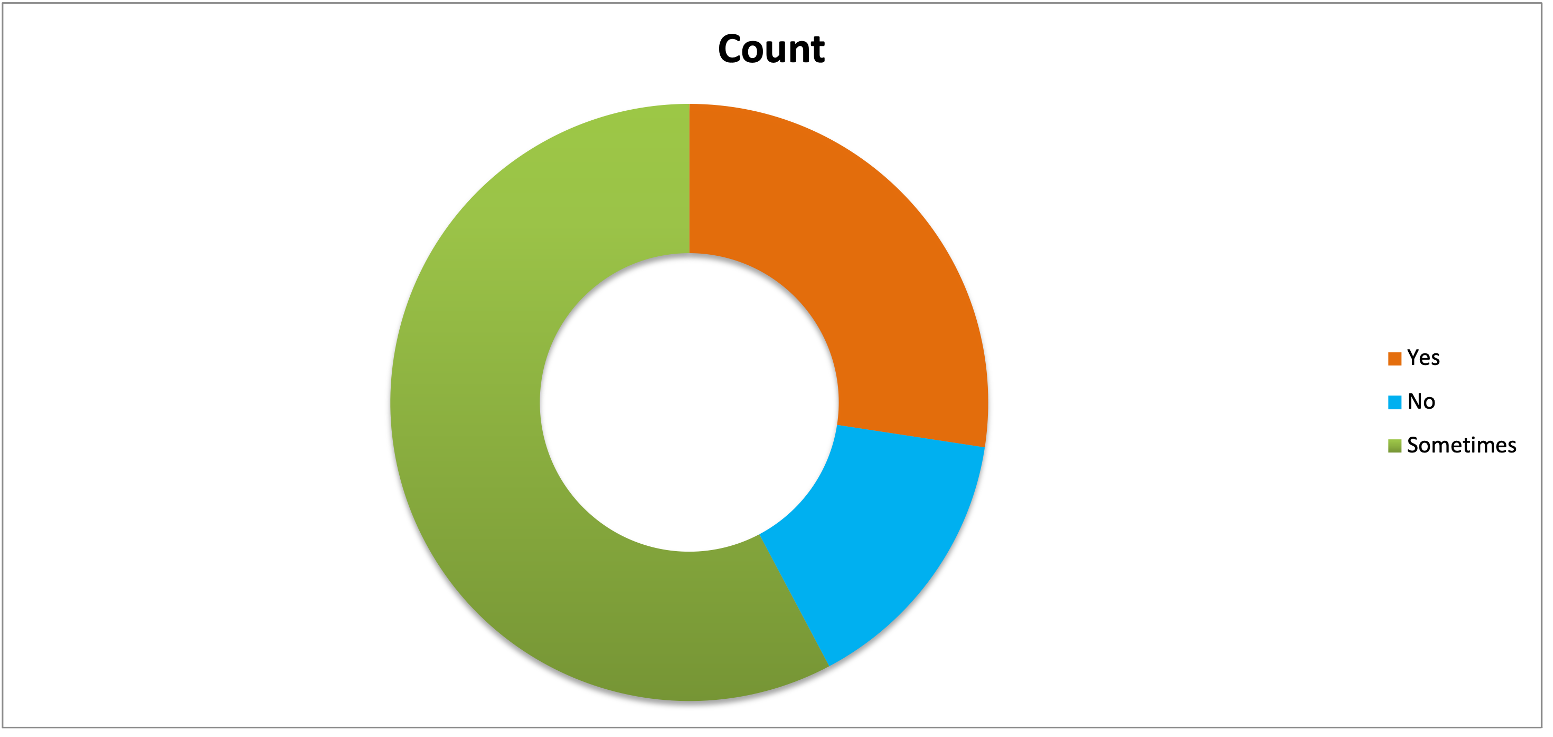

Students seemed equally split when we asked if they considered gen-AI use in academic spaces to be cheating. Again, the data shows that students fall somewhere in the middle of what they are willing to answer regarding this hot-button topic. While 27% answered definitely yes, gen-AI use is cheating, 15% reported definitely no. Overwhelmingly, most students were in the middle ground, with 58% reporting sometimes. The doughnut visualization in Figure 3 shows the “sometimes” responses in green, the “yes” responses in red, and the “no” responses in blue. In terms of generalizing this data, we faced a conundrum. We had no way of knowing what that large percentage of “sometimes” meant to students.

Here is where a mixed methods approach is most valuable when measuring attitudes. As a follow-up to the answers to this question, we asked students to describe why they answered the way they chose. We used Qualtrics Text IQ to perform a sentiment analysis of qualitative responses to this question, using keywords to filter student responses and aligning them to the answers to the previous closed question.

Qualitative Analysis Discussion on First-Year Writers

To measure students’ responses to quantitative questions that had qualitative attitudinal follow-ups, we used Qualtrics Text IQ and dual-rater review to obtain what we believe are accurate and valid sentiments based on keyword analyses. We present several unique findings that help instructors and administrators take a deeper dive to understand what students have on their minds.

Interestingly, when we filtered responses to the question asking students to explain their answer to “AI use is cheating,” the word plagiarism showed up in 25 responses, or 3% of total respondents. While at first pass, this number seems not significant, we argue it is significant for a few reasons:

- We did not use the word plagiarism in the survey at all. Three percent of students equivocated cheating and plagiarism as synonyms.

- Of this three percent, 20% of students who used the word plagiarism answered yes that AI use is cheating.

- Of students who used the word plagiarism to describe AI-usage as cheating qualitatively, 100% of them also answered yes to the quantitative question, giving us an accurate measure.

- Of the students who answered no to whether AI use is cheating, (15%), they also reported in their explanations that “there is nothing wrong with it” at a rate of 80%. More than 13% of these same students who answered that AI-use is not cheating reported that AI-use was like tutoring or writing center visits.

In general, students reported the following phrases (or similar) the most:

- “It’s my words that I put into the bot”

- “It’s unfair for students to use it to get a better grade”

- “We will use it in our work lives so we need to be prepared for it”

- “It’s OK to use it to brainstorm and create but not to copy from”

As we delve further into the data (and as the data set continues to grow), we want to focus on the two questions tied to cheating and perform a deeper sentiment analysis to help us understand these findings.

Another initial finding that intrigued us came in the general feedback question about academic writing. When we filtered results for the word “academic,” that specific word only showed up in general responses 2% of the time. Of that 2%, 78% of those references to the word “academic” were coded as negative sentiment. Example phrases associated with “academic” seemed to indicate that students placed themselves where we have heard some professors anecdotally place them: as not understanding when and how to use generative artificial intelligence (gen-AI) in academic writing.

As researchers studying generative AI, we would be remiss to not utilize these very tools in our own data-dive. For this purpose, we utilized Claude, a large language model (LLM) built by Anthropic, a startup founded by former members of ChatGPT’s parent company, OpenAI. Claude’s robust feedback system and training algorithm, built on a variety of texts including books, articles, and conversations, enables it to understand nuances and relationships in language that we found other LLMs unable to replicate. For this reason, we found Claude to be the most accurate AI assistant for the tasks we assigned.

To effectively demonstrate Claude’s ability to analyze data across sets, we carefully crafted prompts to guide our engagements toward useful output. Our primary strategy involved breaking down our analysis goals into discrete, intermediate steps, improving Claude’s reasoning and response quality, as well as using clear, intentional language and providing relevant contexts. Through these techniques, we obtained the following results in data review and analysis.

Prompt #1 focused on extrapolating specifics of quantitative data from both our first-year composition and technical communication data sets:

- “I'm going to provide you data from a survey of nearly 1,000 first-year college students focusing on opinions about/experiences with AI. Can you synthesize this data? Thank you.”

- “I’m going to provide you data from a survey of undergraduate students enrolled in a 2000-level technical communication course focusing on opinions about/experiences with AI. Can you synthesize this data? Thank you.”

Prompt #2 focused on sourcing and contextualizing significant open-ended responses in relation to this quantitative data:

- “Can you offer up some particularly important open-response answers from the document I provided?”

Prompt #3 focused on testing Claude’s ability to handle more than one text at a time.

- “Now I would like you to provide an expansive cross-analysis of these data sets against one another. Please refer to the first set as the ‘Composition’ set and the second as the ‘TCOM’ set.

Claude’s analysis was consistent with our own findings across all three prompts. With prompt #1, it identified the same key themes we observed--students acknowledging benefits like efficiency, idea generation, and grammar improvement alongside risks like plagiarism and diminished critical thinking. For prompt #2, Claude effectively sourced and framed relevant student insights, reiterating the same trend we see of students valuing AI for assistance but avoiding full reliance for a myriad of reasons. To demonstrate Claude’s capabilities more clearly, we have included its full response to prompt #3 below:

“Absolutely, here is a more detailed cross-analysis between the TCOM student survey data and the Composition student survey data on perspectives about AI in writing:

Usage of AI Writing Tools

- The TCOM survey had higher reported usage of AI writing tools like GPT, with 77% saying they had used them compared to 57% of Composition students.

- In open responses, TCOM students provided more examples of using AI tools in academic contexts (writing papers, getting clarification on assignments) and professional contexts (improving resumes/cover letters, writing work emails).

- Composition students more often reported using AI tools for personal writing and creative pursuits in open responses. Very few mentioned using it for schoolwork.

- This suggests TCOM students may be more comfortable integrating AI tools into their academic and professional writing compared to Composition students. It aligns with TCOM's focus on technical communication for the workplace.

Views on Ethics of AI Writing Tools

- Students across both surveys expressed mixed views on whether AI tool use constitutes cheating.

- In open responses, TCOM students provided more examples of using AI tools in academic contexts (writing papers, getting clarification on assignments) and professional contexts (improving resumes/cover letters, writing work emails).

- The most common perspective was that it depends on how the tools are used. Using AI to generate ideas, improve flow, check grammar, etc. was seen as acceptable, while using it to write full assignments was widely seen as cheating.

- However, a segment of TCOM students (26%) felt AI was not cheating compared to only 9% of Composition students. This ties back to the first point about TCOM students being more open to AI integration in writing.

- Concerns about plagiarism, lack of originality, and undermining the learning process emerged clearly in both datasets. Students value critical thinking skills involved in writing that AI does not provide.

AI Writing Tools' Role in the Future

- TCOM students were more optimistic about AI playing a major role in the future of writing. 60% said it "maybe" would be the future compared to 43% of Composition students.

- Composition students more strongly rejected the idea of AI replacing human creativity and jobs. Many emphasized the importance of emotion, soul, and humanity in writing that AI lacks.

- Still, sizeable segments in both surveys (32% TCOM, 43% Composition) were uncertain if AI would dominate writing. This suggests students have mixed views on if AI capabilities will advance enough to surpass human skills.”

Here, Claude again lays out findings consistent with our interpretation of both data sets, revealing interesting contrasts in attitude between first-year composition and technical communication students.

Collectively, this exercise demonstrates Claude’s ability to accurately assess qualitative data. By engaging in effective prompt engineering, our research team was able to utilize LLM capabilities to produce results consistent with our own research and analysis across more than one data set. Too, we were able to conduct limited cross-analytical work, Claude offering inventory and insight of more than 1,000 responses. More generally, this exercise also highlights gen-AI’s potential usefulness in research processes; surfacing key themes, establishing relevant connections, and transforming data into actionable insights. We hope to expand on these processes with continued research.