Stylistics Comparison of Human and AI Writing

Christopher Sean Harris, Evan Krikorian, Tim Tran, Aria Tiscareño, Prince Musimiki, and Katelyn Houston

Measuring AI Style

Few published studies of AI writing style have been published thus far, and even those that are available to read are primarily in a state of pre-publication. Herbold, et. al. (2023) conducted a comparative analysis of argumentative essays written at the high school level and procured from Essay Forum, a study skills forum in which high school students post essays in hopes of receiving feedback. In the study, 111 teachers rated a total of 270 essays (90 human, 90 GPT-3, and 90 GPT-4 essays) during a training session on AI writing challenges and pedagogy. English as a Second Language students composed the human essays. Participants read essays without knowing who wrote them and evaluated them in six categories including topic and completeness, logic and composition, Expressiveness and comprehensiveness, language mastery, complexity, vocabulary and text linking, and language constructs. In each category, humans received the lowest scores and GPT4 received the highest scores (p. 10). The authors note that the humans may have scored the lowest because they are unknown English language learners with unknown English proficiency. While the results comparing human and machine writers may not be wholly useful, the authors did rate the raters’ ability to detect machine-written text. Of those familiar with Chat-GPT, 80% of respondents could accurately detect AI writing. Of those not familiar with Chat-GPT, 50% could accurately detect AI writing (p. 5).

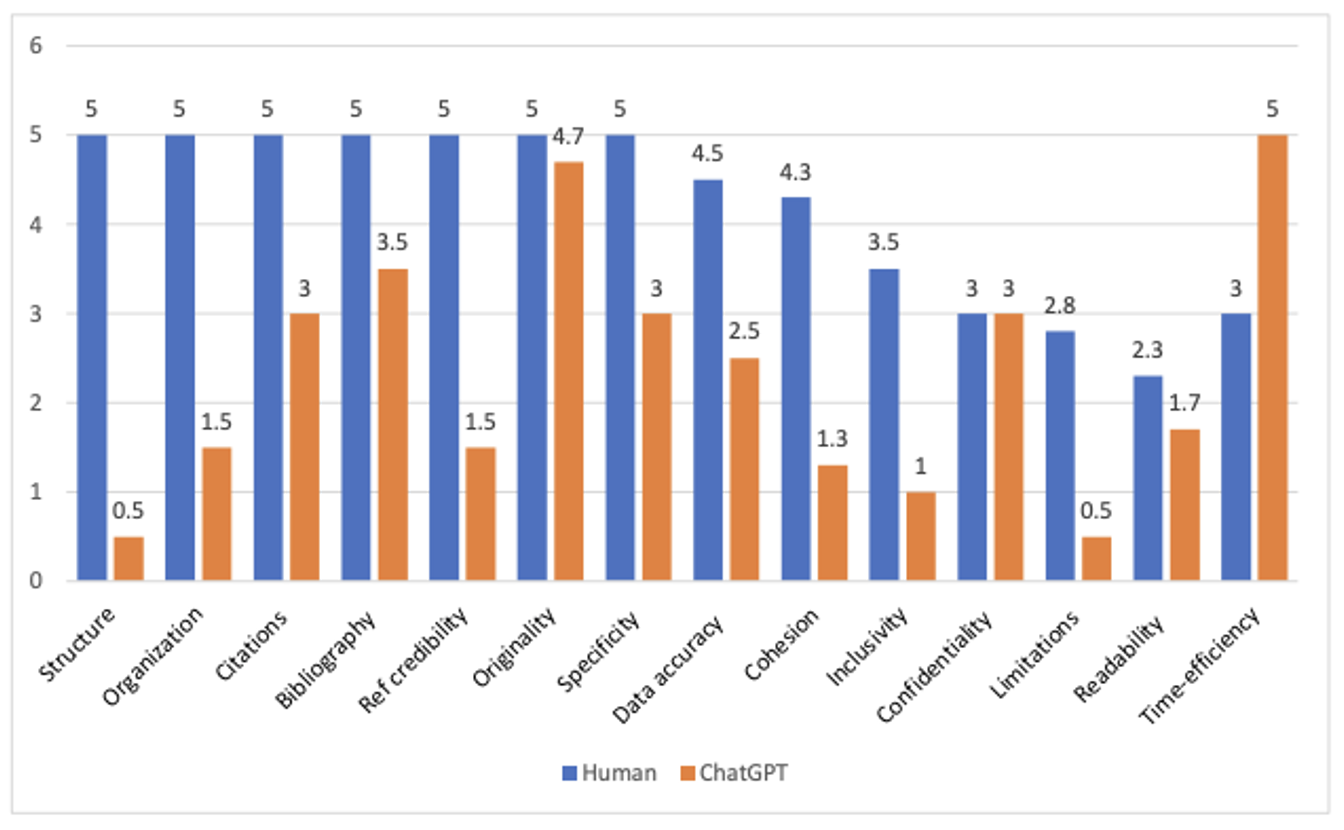

In Pakistan ul Haq, et. al. (2023) compared human-written science writing with machine-written science writing: 500-word structured articles on topics such as human development and communicating COVID-19 protocols. The researchers provided key words in prompting to the AI to ensure it wrote at the appropriate level. Texts were evaluated on 14 criteria ranging from structure to cohesiveness, to time efficiency, and Grammarly was employed to collect some of the data. The raters found that Chat GPT mixed up sections such as methods and discussion and produced rather “perfunctory” texts, though those texts were reasonably believable (ul Haq, et, al., 2023, pp. 6–7). That believability, when paired with public health writing, can be harmful and possibly cause death, warned ul Haq, et. al. (2023, p. 8).

GitHub user Gaelan Steele (2023) reports on how they asked ChatGPT to take the College Board’s AP Computer Science A Exam, and ChatGPT scored a 32/36. Steele’s methodology is notable, as they provided as much of each prompt as possible, excluding data charts or images. In cases with multiple-part questions, Steele fed each part to the AI separately rather than asking it to answer everything all at once. Steele scored the first answer without any additional prompting. ChatGPT made three coding errors in question one and one coding error in question four. In our study, we asked Google Bard and GPT-4 to write Visual Basic macros and Python scripts to collect data. The AI programs were able to trouble shoot their own code if we fed it back to them, but ultimately, we could not get it to recognize words for sentences. We surmise that if Steele prompted the AI further, then it would have caught some of its mistakes.

Given notions of style from both classical rhetoricians and contemporary authors, we are confident that style in writing can be reliably measured and compared. The three AI-writing studies here provide cues as to how to construct a reliable framework, from establishing a systematic process to selecting credible samples. Cardon, et. Al. (2023) advocate for teaching AI literacy by comparing human and machine texts side-by-side with students, and our studies provide models for how to do so.